Geopolitical Analysis

The Crucible: Europe, Islam, and the Forging of the West

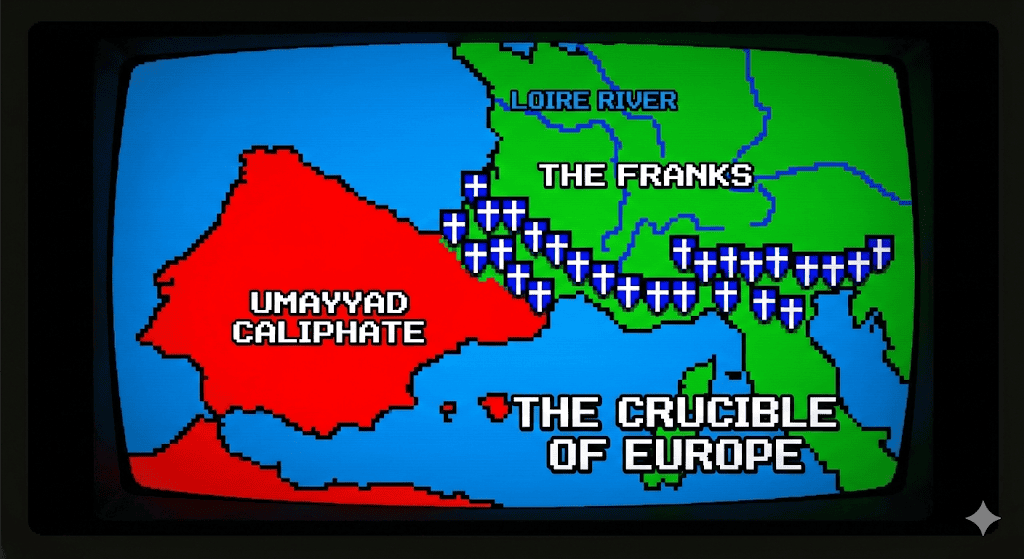

OPERATIONAL CONTEXT: The transformation of Europe from the late Antique Roman system into the feudal decentralized structure was profoundly shaped by the rapid expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate in the 8th century. This dossier analyzes the kinetic collision that dismantled the old world and forged the new.

// SECTOR 01: THE COLLAPSE OF HISPANIA (711 AD)

In 711 AD, the Umayyad commander Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed the narrow channel separating Africa from Europe. He landed at the mountain that now bears his name: Jabal Tariq (Gibraltar).

The collapse was total. The Visigothic Kingdom, weakened by internal succession crises and civil war, shattered at the Battle of Guadalete. Within seven years, the Caliphate’s forces had swept north, capturing the capital Toledo and reaching the natural barrier of the Pyrenees Mountains. This marked the end of Roman-Christian rule in the Iberian Peninsula for 700 years.

System Architecture: The Pax Romana (Legacy System)

The collapse was total. The Visigothic Kingdom, weakened by internal succession crises and civil war, shattered at the Battle of Guadalete. Within seven years, the Caliphate’s forces had swept north, capturing the capital Toledo and reaching the natural barrier of the Pyrenees Mountains. This marked the end of Roman-Christian rule in the Iberian Peninsula for 700 years.

SYSTEM FAILURE:

The speed of the Islamic conquest dismantled the fragile post-Roman political structures. The centralized bureaucracy vanished, creating a power vacuum in the West that allowed local strongmen (warlords) to rise.

// SECTOR 02: THE MEDITERRANEAN CLOSURE

As the Caliphate consolidated control over North Africa, Spain, and the Mediterranean islands (the "Internal Lake" of Rome), the ancient trade routes that sustained the European economy were severed.

The Pirenne Thesis: Without the flow of papyrus, gold, and spices from the East, the Merovingian economy collapsed. Gold coinage disappeared, replaced by silver. The center of European gravity shifted away from the Mediterranean coast, moving North to the Rhine and the Seine—the heartland of the Franks.

The Pirenne Thesis: Without the flow of papyrus, gold, and spices from the East, the Merovingian economy collapsed. Gold coinage disappeared, replaced by silver. The center of European gravity shifted away from the Mediterranean coast, moving North to the Rhine and the Seine—the heartland of the Franks.

ECONOMIC MUTATION:

The loss of liquid capital forced a shift to a Land-Based Economy. Wealth was no longer measured in coin, but in soil and service. This necessity paved the way for the decentralized power system known as Feudalism.

// SECTOR 03: THE HAMMER (732 AD)

In 732 AD, an Umayyad expeditionary force led by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi crossed the Pyrenees into Aquitaine (Southern France), crushing resistance and sacking Bordeaux. Their target was the wealthy Shrine of St. Martin in the city of Tours, deep in Frankish territory.

Blocking their path on the old Roman road between Poitiers and Tours was Charles Martel ("The Hammer"). Unlike the disorganized Visigoths, Martel commanded a professional, hardened infantry force.

Blocking their path on the old Roman road between Poitiers and Tours was Charles Martel ("The Hammer"). Unlike the disorganized Visigoths, Martel commanded a professional, hardened infantry force.

TACTICAL ANALYSIS: THE INFANTRY SQUARE

Martel deployed a revolutionary tactic against the superior Umayyad cavalry.

- Terrain Usage: He chose the high ground, using trees to break the momentum of the cavalry charge.

- The Phalanx: His heavy infantry formed a tight shield wall—a "wall of ice"—that refused to break under repeated charges.

- Strategic Discipline: Unlike other armies that broke ranks to loot, Martel's troops held the line. When the Umayyad commander was killed, the invasion force dissolved and retreated south.

HISTORICAL OUTCOME:

The Creation of "Europe": The conflict provided a powerful political rallying point. It legitimized the Carolingian dynasty (Martel's descendants, including Charlemagne) and forged a cohesive, self-aware "European" identity distinct from the Byzantine East and the Islamic South.

// SECTOR 04: DIVINE PRE-EMPTION (THE LONG GAME)

When viewed through the lens of divine geopolitics, the events of Acts 16 take on staggering significance. In 50 AD, the Apostle Paul attempted to push the Gospel deeper into Asia (modern Turkey). The Holy Spirit explicitly forbid him, redirecting him instead to cross the Aegean Sea into Macedonia—into Europe.

Why? Because the Omniscient Commander knew the map of the future. By the 7th century, the great Christian centers of the East—Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and eventually Constantinople—would be overrun and subjugated by the rise of Islam.

Mission Analysis: The Macedonian Call

Why? Because the Omniscient Commander knew the map of the future. By the 7th century, the great Christian centers of the East—Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and eventually Constantinople—would be overrun and subjugated by the rise of Islam.

THE BACKUP SERVER:

God was proactively establishing a "Fortress" in the West. By forcing the Gospel into Europe centuries before the threat emerged, He ensured that when the Eastern "servers" of Christianity were compromised by the Islamic conquest, a robust, hardened "backup server" in Europe would be ready to preserve the faith. The Frankish victory at Tours was not just a military win; it was the successful defense of this divine contingency plan.

// SECTOR 05: THE ATLANTIC BREAKOUT

The adversary, operating through the geopolitical entity of the Caliphate (and later the Ottomans), successfully bottled up the European peninsula. They controlled the Silk Road and the spice trade, bleeding Europe dry of gold and isolating Christendom. This was a "containment strategy" designed to wither the vine of the Church.

But pressure creates diamonds. The inability to go East forced Europe to look West and South. It triggered the Age of Discovery.

Logistics Analysis: The Spice Trade Blockade

Adversary Profile: The Melqart/Allah Connection

But pressure creates diamonds. The inability to go East forced Europe to look West and South. It triggered the Age of Discovery.

THE FLANKING MANEUVER:

By attempting to strangle Europe, the adversary inadvertently forced the Gospel to go global.

- The Atlantic: Columbus, seeking a route to break the Islamic trade monopoly, carried the Cross to the Americas.

- The Cape: Vasco da Gama outflanked the Islamic blockade by sailing around Africa, opening the East to direct contact.